In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

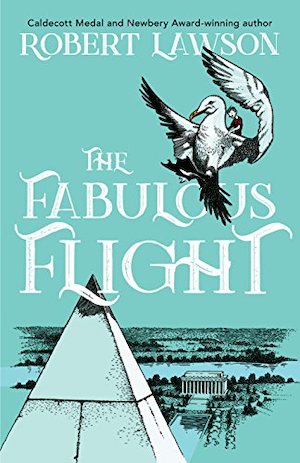

In everyone’s young life, you encounter books you will remember forever. Sometimes you will keep the book, and even read it with your own children. Other times, it might be someone else’s book, or a library book, that you find once but never see again. One of those books I encountered in my past, and tried to find for years, was Robert Lawson’s The Fabulous Flight. It’s the story of a young boy who shrinks until he is only a few inches tall, befriends a seagull that takes him to Europe, and becomes an intelligence agent for the U.S. State Department. The premise sounds preposterous when reduced to a single sentence, but it turns out to be a captivating tale, full of clever details and subtle humor.

I found The Fabulous Flight in my local library in Ellington, Connecticut. I’ve discussed that library in this column before, because it is where I found Andre Norton’s The Beast Master (find the review here). I had tried for years to remember the title of this book, and the name of its author, so I could read it again. A few weeks ago, trying to stir my memory, I closed my eyes and tried to picture the library. Soon, I could almost see it, with the children’s room off to the right side of the front desk. I remembered the way sound echoed off the marble, tile, and woodwork. And I remembered the musty smell of aging paper, and the sharp scent of the shellac on the wooden shelves, which sometimes got tacky on humid summer days. I remembered the book being shelved by a tall window, and the way sunbeams came through that window in the afternoons. And that the book was near a radiator that sometimes hissed in the winter. And then, finally, just when I thought this exercise was futile, the author’s name came to me: Robert Lawson.

A quick online search brought up the title, and then I found that just a few years ago, an outfit named Dover Publications had reissued it in a nicely bound trade paperback edition—and with all its illustrations intact, which was quite important to me. A few clicks later, a copy was on its way to my house (I may be old-fashioned enough to still read all my books on paper, but there are some aspects of modern technology I find very useful).

About the Author

Robert Lawson (1892-1957) was an American author and artist known primarily for his children’s books. He also did freelance artwork for magazines and greeting card companies. He won a Caldecott Medal for illustrating the book They Were Strong and Good, and a Newbery Medal for his book Rabbit Hill. His work was first published in 1914, and during World War I he put his artistic talents to work as a member of the U.S. Army’s 40th Engineers, Camouflage Section. Two notable works led to cartoons produced by Disney; Ben and Me: An Astonishing Life of Benjamin Franklin by His Good Mouse Amos, adapted as Ben and Me, and The Story of Ferdinand, adapted as Ferdinand the Bull.

Lawson’s stories were often humorous, and frequently featured historical figures, stories from fantasy and legend, and talking animals. While he wrote and illustrated many of his own books, he also worked extensively as an illustrator of works by others. His precise and detailed inks lent themselves to excellent interior illustrations. The Fabulous Flight, published in 1949, stands as his clearest foray into the world of science fiction.

The Art of the Interior

Artwork has been important to science fiction longer than we’ve used the term “science fiction.” Stories that describe peoples, places, and things that have never been seen before tend to benefit greatly from the support of illustrations. The pulp magazines, where modern science fiction came of age, were full of illustrations, not only on the covers, but with black and white interior illustrations that marked the start of a new story, or appeared among the columns of text. Pulp stories didn’t have a lot of room for detailed descriptions, so the art gave readers valuable information on the characters, their spaceships and devices, and the strange new worlds they visited.

When I was first cutting my teeth on books, I loved the ones that had illustrations, be they on dust jackets, in frontispieces, or on the pages themselves. Children’s books like The Fabulous Flight, with its crisp, draftsman-like line work, were more fun and approachable than books without illustrations. And when I graduated to reading my dad’s science fiction magazines, like Analog and Galaxy, I found wonderful illustrations by artists like Kelly Freas, John Schoenherr, H. R. Van Dongen, and Leo Summers. I talked about some of those illustrations in my review of Harry Harrison’s Deathworld. Fortunately for fans, illustrations were not left behind when the pulp magazines died out.

Especially in fantasy books, there is nothing like a good map to make you feel like an imaginary world is real. I can’t imagine reading the works of J.R.R. Tolkien without that map in the front of the books to consult. And as a youngster without an extensive knowledge of geography, I found the map in the front of The Fabulous Flight to be quite useful.

Even today, I still look for books with interior illustrations, something I noted in my recent review of Greg Bear’s Dinosaur Summer, a beautifully illustrated book. One of my big disappointments with the new Star Wars: The High Republic adventures, which include books for all ages and comic books as well, is that the publisher didn’t take advantage of all the artists on hand to include illustrations not only in the books for younger readers, but also in the books intended for older audiences. Particularly in books with large casts of characters, thumbnail illustrations here and there in the text can be quite useful.

The Fabulous Flight

Peter Peabody Pepperell III stops growing when he’s seven years old. And then begins to shrink. It is hardly noticeable at first, but before long it’s undeniable. Something to do with his sacro-pitulian-phalangic gland, suspects his doctor (it’s a gland I couldn’t find on the internet, so I suspect it was created just for this book). He had fallen out of a tree about the time he started to shrink and hurt his chest, but while the doctors suspect another sharp blow might reverse the process, it could also cause him severe harm. So everyone in the family prepares to live with this new status quo.

His father, an important official in the State Department, looks forward to Peter’s small size coming in handy in his workshop, a wing of their large house where he builds all sorts of models, and has a massive model train layout (I remember being extremely jealous of that workshop). Peter’s mother, who comes from a military family, is sad that this might prevent Peter from becoming a general or colonel, although she consoles herself that at least he won’t become a major, a rank that she (for some reason) loathes. As Peter shrinks, it becomes impossible for him to continue in school, so a Pepperell niece, Barbara, comes to tutor him.

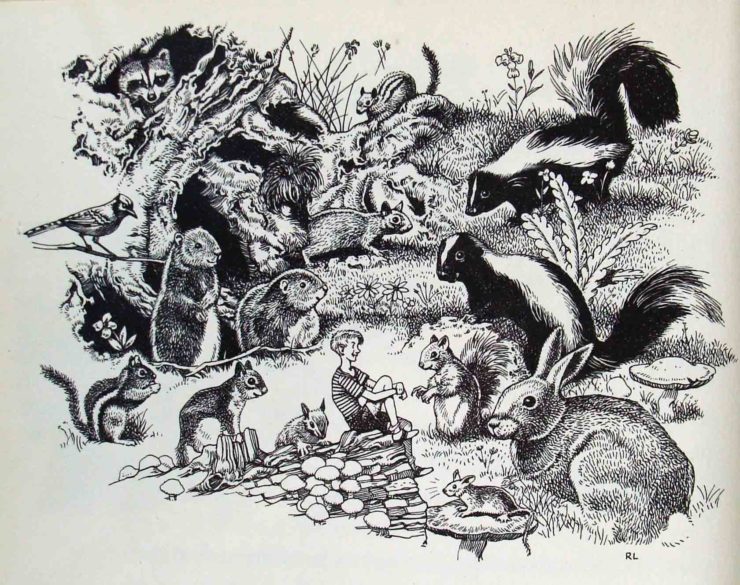

Buy the Book

Seasonal Fears

Eventually, Peter shrinks to the approximate size of a chipmunk, and through a process that is not explained to the reader, develops an ability to communicate with the animals in their yard. A large rabbit named Buck becomes a favorite friend, and allows Peter to ride upon him; Peter’s father makes him a tiny saddle and set of chaps to facilitate this. They have a run-in with a couple of fierce beagles, so Peter’s father makes him a pair of tiny revolvers, loaded with blanks that should make enough noise to scare off predators. Peter gets the idea to organize the animals (who include mice, chipmunks, skunks, squirrels, and frogs) into a military unit, and with his father’s help, soon has artillery, caissons, ambulances, and supply wagons. Peter presides over their maneuvers astride his noble Buck. He even organizes the local birds into airborne units. Peter decides to entertain one of his parents’ garden parties with his military maneuvers, but the guests are unprepared for the drill, and chaos ensues.

By the time Peter is thirteen, he is only four inches tall, and his father builds a miniature sailing yacht that he enjoys taking out into their pond with a crew of field mice. There he meets a seagull from Baltimore named Gus. Gus is a little rough around the edges but very friendly, and soon offers Peter a chance to ride on his back; within a few days, he takes Peter soaring over Washington, D.C. Coincidentally, that very evening, Peter’s father confides in his family that a scientist in the European nation of Zargonia has developed an explosive whose destructive power dwarfs that of atomic bombs. The scientist and his explosives are hidden away in an impenetrable fortress, ringed with troops and defended by fighter planes.

His father can’t see any way to neutralize this threat. But Peter has an idea. Flying on Gus, he could slip in and out of any fortifications undetected. Peter’s father is intrigued by the idea, and the next day, while he is at work, Peter asks Gus to fly him to Washington, D.C. once again. They fly into a window at the State Department, and Peter pitches his idea directly to the Secretary of State himself. Thus, Peter soon finds himself enlisted for a secret mission.

As a youngster, I found this fascinating, but as an adult, I found it unsettling. Send a 13-year-old on a potentially deadly mission? Peter’s father is a bit eccentric, and tends not to think of things in terms of risk, even when those risks should be obvious. At least Peter’s mother has misgivings, although she puts her feelings aside due to her experience as part of a military family. Peter’s father builds a pod to strap on Gus’ back—and here the illustrations, which have livened up the proceedings throughout the book with images that include armies of backyard animals, really come to the fore. The capsule they construct is absolutely lovely, and fascinating in its details. It has the elegant lines of the cockpit of a P-51 Mustang, and there is one drawing in particular, showing it being loaded for their journey, which is so evocative that I remembered for years. They even make Peter a miniature sword that is actually a hypodermic needle, where the blade is the needle and the grip is a squeeze bulb filled with an anesthetic strong enough to knock out a grown man.

The trip to Europe is a big part of the book’s fun, as Lawson takes the time to describe their ocean journey and every city in detail. Gus’ down-to-earth observations during their travels are entertaining, and Peter’s excitement at seeing so many new things is contagious. There is a map in the front of the book that I kept turning back to as they traveled, another little element that made the narrative feel realistic. When they finally reach the castle in Zargonia there are some twists and turns that keep the reader guessing, and also keep the story from turning too dark.

I won’t go into more detail in order to avoid spoilers, but will say this is an absolutely delightful adventure story that I would recommend to young readers today. There are a few details that are dated and firmly place the story in the years that immediately follow World War II, but the book feels remarkably fresh.

Final Thoughts

I am so glad I finally tracked this book down. I wish I’d found it again when my son was young, so I could have shared it with him. It is a gem, and in fact, I’d recommend any of Robert Lawson’s books for young readers of today.

From those who remember The Fabulous Flight, I’d love to hear your recollections and opinions. And from others, I’d love to hear what illustrations and illustrators you have enjoyed encountering, and what stories caught your fancy when you were young.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

Have to agree with you on illustrations – I always felt that they added to the story when done by a good artist. It’s a pity we see so little of this these days.

Frank Pape’s illustrations in Cabell’s Poictesme novels are a good example, even though they definitely aren’t suitable for youngsters.

It sounds delightful!

My family’s copy of the Borrowers had illustrations which I really enjoyed growing up.

A few other examples: The Story of Ferdinand (as illustrated by Robert Lawson!), anything by Robert McCloskey, the lovely illustrations in the Little House series drawn by Garth Williams.

Oh, and the art in the Hank the Cowdog books.

I have very fond memories of this book myself, and also managed to track it down as an adult–although my edition is not one of the nice reissued ones. That’s fine–it’s closer to the library book I read as a child.

I never really enjoyed Ben and Me for some reason (must revisit, though!), but I adored another of his historical-figures-and-animals books, called Mr Revere and I: Being an Account of certain Episodes in the Career of Paul Revere, Esq. as Revealed by his Horse

The horse in question, Scheherezade, used to be a cavalry mount for the British, and felt herself to be very grand and full of pomp and circumstance, so when she ends up gambled away into the hands of this yokel colonial she’s not happy about it. I read it literally to pieces. I still have my copy, and it’s held together with rubber bands.

Would love to read it just for the fierce beagles–I’ve never met a “fierce” beagle in my life! 8-D

But when you’re that size, I suppose they would be.

I haven’t thought about this book in half a century and didn’t even recognize the title — but the description rang a bell loudly; I remember loving the story. ISTM there was a lot of contemporary-techno work for kids back then that wasn’t treated (e.g., shelved) as SF because it was contemporary, however improbable; e.g. The Trouble with Jenny’s Ear (she turns telepathic), or Mr. Twigg’s Mistake (another Lawson), in which unmixed pet food causes someone’s pet mole to grow to human size, or the Danny Dunn books…. (ISTR those coming up on tor.com but a simple search doesn’t find any mentions.) I may have found this book because of the author’s series of colonial-history-seen-by-close-animals books; in addition to yours and @ergative’s, I remember one that Lawson’s Wikipedia entry tells me was Captain Kidd’s Cat.

The library where I found these books no longer exists — it was part of the ~50% of my childhood school that disappeared in successive overhauls — and the replacement seems thin by comparison; I wonder whether the interwebs provide not the same kind of browsing experience but the same sense of discovery of something to get away into. The word-of-mouth popularity of the first Harry Potter book isn’t really comparable; I remember recommendations, but also wandering through stacks and reading bits of books until I found something that appealed. (I certainly wasn’t checking dates, and had no idea the author had died before I learned to read.) The net does make finding current stuff easier in some ways; how does it do on works that aren’t current but aren’t old enough to have fallen off of library shelves?

@5 The Enormous Egg is another example of what you refer to – kid’s books that have a speculative element but are kept on the shelves with the regular stuff. As a dinosaur-besotted youngster, this one was a real treasure for me. When I found a copy in a library clearance sale, I grabbed it.

And the pleasure (and potential usefulness) of simply browsing through the stacks is becoming a thing of the past. Even my university library, where you used to be able to nose about and maybe, serendipitously, find something useful, has most of its holdings now in high-density storage off-campus, and you have to ask for any book by name if you want to check it out. They’re very efficient about delivery – one day – but that element of happy chance and random discovery is gone.

@6 The Enormous Egg is one of my favorites, as is Lawson’s Rabbit Hill, a “cozy fantasy” that is the feel-good version of Watership Down

@7 – nice to see someone else liked it. I’ve never encountered anyone else who’d read it at all.

@7, 8 – My mother read the Enormous Egg to I and my siblings. I don’t really remember the story, but we all enjoyed it.

Oooh! Danny Dunn books and The Enormous Egg. Those are names I’ve not heard in a long time. And a book about a mysterious mushroom planet also tickled my memory as I thought back on those old favorites. I’ll tuck them away as ideas for future reviews that take us on a trip down memory lane.